There's something it feels like to be a bee

There's something it feels like to be a bee

So it turns out that bees appear to be thinking, feeling creatures. Individual bees have personalities (some are far more industrious foragers than others, for example, even when closely related).

Bees can count. Bees can learn from one another. Bees can use simple tools. Bees sleep (and likely dream... of flowers?) We can design studies to show that bees feel optimism or pessimism, depending on what's happened to them lately. Bees make choices, plan for the future, form mental maps so as to find their way across changing landscapes from home to flowers and back, and even exhibit playfulness.

Although their brains are incredibly small—just one million neurons compared to humans’ 100 billion—bees have remarkable abilities to navigate, learn, communicate, and remember. Bees plan for the future, think and form mental maps, make choices, and exhibit playfulness.

"Bees spend a good deal of time sleeping, during which memories are formed and stored in long-term memory just as in us. It may be impossible to ever know, but bees may even dream."

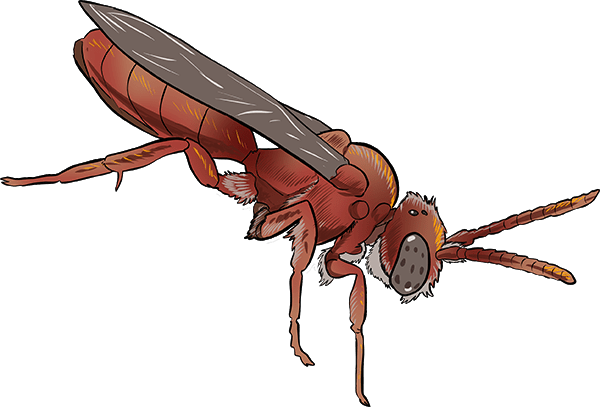

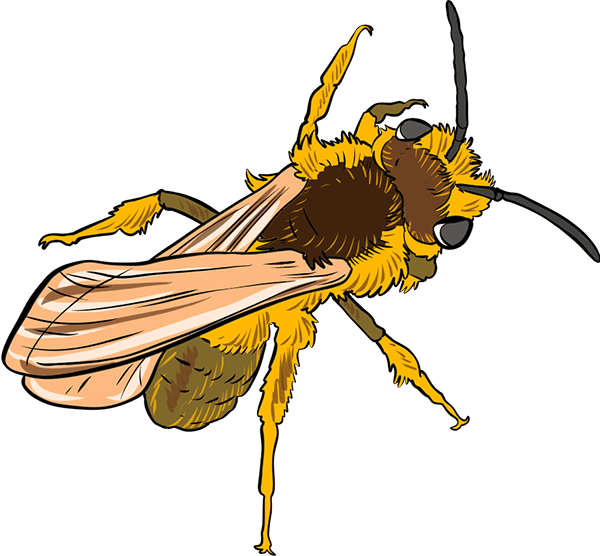

Bees are also incredibly diverse: there are 21,000 or so species of bees (metallic green and blue bees, fuzzy teddy-bear-ish bumble bees, sleek red and black cuckoo bees... and more)!

There are only 7 species of honey bee by the way (for all their social lifestyle is so well-known). Most bees live nothing like honey bees with their hives, a queen, a handful of drones, and tens of thousands of worker bees. Bumble bees (of which there are around 250 known species) do have queens and workers, but most bees live full lives, finding their own mates.

We all have our own morning routines!

This leaf-cutter bee spent a good hour cleaning and stretching as he warmed in the summer sun, breakfasting on occasional sips of nectar. Did you see him flash his ultra-fuzzy front legs? These exude his own special scent, which he massages over his mate's antennae.

Why are bees in trouble?

Why are bees in trouble?

Many pollinators are disappearing at alarming rates, especially wild bees. Almost all are declining in abudance and diversity, be they bumble bees, solitary bees, or other semi-social bees (social behavior in bees exists on a continuum, and may even differ within a species, depending for instance on the availability of nesting resources).

Bees have fairly simple needs: abundant and diverse flowers through the seasons, and places to call home where they may raise the next generation. But the problems bees face are no longer simple:

- Healthy food sources and places to nest are disappearing, with “pollinator deserts” replacing once abundant flowering meadows and other naturally diverse wild places.

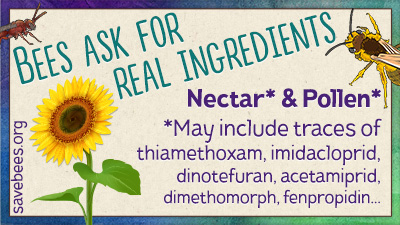

- Pesticides are weakening pollinator immune systems, leaving them more open to diseases and parasites.

- People are moving honey bees and bumble bees around commercially, narrowing their genetic diversity and spreading bee parasites and pathogens in the process.

- Climate change is disrupting once-predictable patterns (for instance, many types of bees have evolved to time their emergence for when specific sorts of flowers are in bloom).

Pesticides are highly detrimental to many bees, causing both acute and chronic effects: anywhere from death to shortened lifespans, weakened immune systems, and impaired memory and learning.

For many bees, habitat loss is possibly the most critical issue they face. Many once rich habitats are gone, with losses of 97-99.9% of native wildflower habitats over the last 50-150 years (depending on where you look), primarily due to increasing agricultural intensification. Bees evolved for such a different world than the modern one, a world in which flowers and nesting sites were plentiful.

Sometimes the main issue is the introduction of species outside their native ranges. For instance, populations of certain bumble bees in the western United States collapsed when imported bumble bees started being used in commercial pollination there. These non-native bees (often raised in poor conditions) spread novel pathogens to native bees, causing quick collapses in populations (by close to 90% since the '90s).

For certain bees that time their emergence with specific flowers (particularly in deserts, which surprisingly host some of the highest levels of bee diversity), climate change may be one of their biggest challenges. Climate change also threatens bumble bees, which have evolved fluffier bodies that they struggle to cool above 108°F (42°C). Although bees can still forage on hot days so long as they only go out early in the morning or late in the evening, these reduced opportunities mean less food.

When factors are combined in the real world—such as habitat loss being coupled with ongoing pesticide exposure, novel pathogens, and climate change—bees struggle to survive under increasing levels of stress.

The good news is that anyone, anywhere can help save bees!

You don't need a hive to help bees!

Honey bees are social pollinators that live in hives numbering tens of thousands. Most bees live totally different lives, often solitary. Keeping hives healthy requires a great depth of knowledge (not to mention dogged tenacity in these un-bee-friendly times)! It's no surprise that beekeeping runs in families for generations.

That's not to say honey bees aren't in trouble: reported rates of colony loss between April 2020 and April 2021 were the second-highest loss rates recorded since they were first tracked in 2006: almost 50%. It's a testament to beekeepers' resilience and adaptivity that we still have sufficient hives providing pollination services. Our current chemical-input-intensive, large-scale commercial agricultural system requires vast honey bee numbers, hence the commercial beekeeping industry: California's 1.6 million acres of almond orchards require 48 billion individual honey bees!

The other issue with folks taking up hobby beekeeping is that increasing honey bee densities can have a negative impact on native bees, unless you're prepared to provide great swathes of additional flowers throughout the season (for all the tens of thousands of honey bees in your hive). A single honey bee hive potentially outcompetes 100,000 native bees for pollen and nectar. It's better to leave beekeeping to experienced beekeepers, and focus on the many other ways you can help our pollinators!

Help bees in your garden, community plot… even a balcony

Help bees in your garden, community plot… even a balcony

Plant native wildflowers and flowering shrubs in your backyards, communities, and workplaces. If you have room, trees such as apples, pears, plums, and cherries (and shrubs like blueberries) are excellent food sources for pollinators, as are many vegetables and herbs.

If you have a lawn, stop mowing some portion… you’d be surprised what flowers will drop in over time. Sow clover (white clover may even be mowed at highest setting). Let dandelions live! They’re one of the first pollen-rich sources to spring up, and also one of the last to go. Because of the shape and structure of dandelions, their pollen and nectar are especially accessible to a great diversity of bee species throughout the year.

Even small balcony gardens help pollinators passing by. Try adding hanging baskets, potted native plants, veggies/herbs, and a small dish of water with pebbles.

Offer more than just food for bees

Offer more than just food for bees

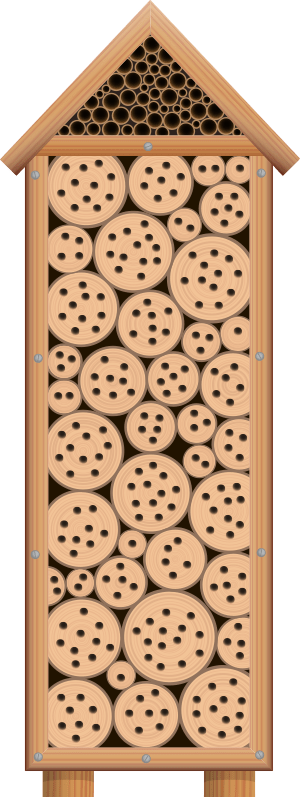

Provide homes for native bees. Did you know that most bees nest in wood, dried stems, or in the ground? Provide bare, sunny soil for mining, sweat, and other ground-dwelling solitary bees. Offer wooden bee blocks, paper straws, or bundles of bamboo for mason, leaf-cutter, and other wood-cavity nesting solitary bees. For mason bees, make sure there’s a source of mud nearby in early spring.

Keep part (or all!) of your garden untidy, which makes more room for wildlife. Pieces of wood in a pile provide shelter and a place for some solitary bees to nest. Dead plant stems are the perfect spots for the young of other native bees to overwinter. Leave a patch of closely-mown or bare soil in a sunny location, important for our many ground-nesting bees.

In summer, place a shallow dish of water out with some pebbles in it, so that bees (and other insects) can easily drink without drowning (bees get thirsty too, and honey bees use the water to help cool their hives on hot days).

Support pollinator-friendly farming

Support pollinator-friendly farming

Support smaller, local, organic farms. Organic farms tend to support higher biodiversity and better bee health. There are industrial-scale organic farms that are still not great for the environment, however. Ideally, sustainable and resilient agroecological farming methods will replace current farming methods.

Agroecology takes an ecosystem perspective on food production, considering the complex ecological web of interactions—including soil health, water and air quality, integrated pest and disease control, and biodiversity. When you think about it, “conventional” industrial farming is a recent development—following on the Second World War—in a long history of human agriculture going back around 10,000 years.

Grow some of your own food. Flowering vegetables, fruits and herbs make excellent variety in pollinator diets. Tomatoes are especially easy and fun for children to grow, and are a great way to help bees, because there’s a dark secret to commercial tomatoes: growers frequently import bumble bees for pollination services (keeping them within their greenhouses). Not only are imported bumble bees implicated in the drastic decline of native bumble bees (when a few inevitably sneak out), but the queens are caged to prevent them forming new colonies, and all bumble bees are incinerated after 8 weeks of hard work. 😢

Buy certified organic cotton (even though you don’t eat it!) Cotton flowers attract bees, but cotton ranks among the highest in pesticide usage on crops, with a mix of pesticides and fungicides known to be dangerous to bees.

Love honey? Buy from local beekeepers who care about their honey bees (find them online or at farmers’ markets). There are so many delectable flavors in honey, try tasting some local varietals!

Tech solutions versus real bees

Some folks favor technological solutions (such as robotic bees). The idea being that we'll develop robotic bees, in case of a shortfall in pollination owing to environmental losses of real bees.

History suggests that robotic bees would come with unintended consequences. Real bees are highly efficient pollinators, fully self-sustaining (with simple requirements), self-powered and replicating, as well as biodegradable when they fail (of old age).

Flowers and bees are also both incredibly diverse, with many individual species of plants adapted to only certain sorts of bees. Bees vary in their pollination capabilities: some have long tongues that plunge into tubular flowers, others vibrate their flight muscles to shake pollen loose. Honey bees—the world's best-known insect pollinators—can't pollinate tomatoes, for example. The technological challenge is far greater than simply designing and powering a tiny flying device attracted to flowers.

Robotic bees would never fill the ecosystem role that bees would leave behind either. Bees naturally serve as important food sources for a wide range of other creatures: both the bees themselves during all their life stages, and also what they store in their nests (be that honey and pollen for social bees, or more primitive mixtures of nectar and pollen, as many types of less social bees provide for their young).

Can Robobees Solve The Pollination Crisis? (Xerces Society blog)

And just a few more ideas…

Participate in citizen science pollinator projects. Various projects will take you into the great outdoors, planting flowers, recording bee sightings, and looking for bee nesting sites. They’re fun projects to share with your family and your neighbors, to get everyone thinking about bees. And having citizen science records is proving incredibly useful for scientific research into helping bees!

Learn more about bees and the challenges they’re facing. They are amazing little creatures, and there are thousands of different kinds of bees, all with their own unique life stories. Spread the word to those around you!

Say no to pesticides! They're never perfectly targeted, and there is almost always more harm done than anticipated: cumulative effects, synergisms, and other unintended consequences. We are poisoning the earth itself, along with all living beings: borrowing from the future, at a heavy cost.

Wondering who's writing this?

I’m Elise Fog, a lifelong bee lover and hobbyist photographer. It struck me (more than ten years ago!) that it’d be cool to share the bee love with others. Bees are a wondrous and vital part of our world, and it wouldn’t look the same without them.

Bees also live pretty much anywhere humans live, so the actions that folks take have a direct local impact on saving bees worldwide. There are so many little actions that, if everyone took just one or two, would really add up for the world’s bees.

I’m not associated with any company or entity, and I’ve written everything on this website myself (unless directly attributed in the text to another person). I’ve carefully vetted each link, with an eye to sharing the most interesting stories and the latest bee science. Curious about me? I’ve written a little more about myself here.

All the Buzz!

An occasional email newsletter with seasonal bee gardening advice, curious bee facts, current bee research, and other bee-related goodness.

I only use your email address to send you occasional bee-related emails (opt-out anytime). Read my full privacy policy.