Are bees in danger of extinction?

Are bees in danger of extinction?

Yes, some bee species have already gone extinct, and many others are threatened with extinction. Up to 50% of all European bee species and between 1/4 and 1/3 of bumble bees worldwide are at risk of extinction. The rusty-patched bumble bee was listed under the Endangered Species Act at the end of 2016, having lost about 87% of its range compared to the late 90s. Franklin’s bumble bee, a once common sight in California and Oregon in the 50s, hasn’t been spotted since 2006.

The gorgeous bright-orange Patagonian bumble bee (so large some have affectionately called it the “flying mouse” and “flying teddy-bear”) is listed on the IUCN Red List as endangered, and ever more bumble bees are declining globally. Seven species of Hawaiian native bees have been added to the Endangered Species List. Honey bees are not going extinct, but annual losses continue to be incredibly high; beekeepers across the United States reported losing 45.5% of their managed honey bee colonies between April 2020 through April 2021. Many other types of bees are in serious trouble, and some are going extinct without our even noticing them 😢

Why do we need bees?

There are around 21,000 known bee species worldwide, of which over 250 are known bumble bees, and only 8 are honey bee species (though depending on whom you talk to, it might be as many as 11, but 8 is the current consensus among taxonomists). 3,600 different types of bees call the United States their home (Australia is home to 2,000 species, and there are around 270 species in Britain).

Bees are keystone species, meaning they’re a vital component of ecosystems. One in three bites of food we eat is thanks to insect pollinators, and 75% of our crops rely on pollinators. Think coffee, nuts, seeds, berries, fruits and vegetables (and even many of our oils). Many of our most nutritious foods are pollinator dependent.

Managed honey bees are important crop pollinators (especially because they’re easily moved around), but equally important are bumble bees and other bees capable of a special technique called “buzz pollination”, without which our tomatoes, potatoes, and blueberries (among other plants) would not set nearly as much fruit.

The many native wild bees throughout our landscapes are critical too, not just for providing diversity in our pollination services, but some are specialists uniquely adapted to pollinating certain plants (squash bees, for instance). Bees are also critical pollinators of alfalfa and clover, so they’re even involved in feeding our pasture animals.

Without bees, we would face an impoverished diet (lacking in vital nutrients), food chains depending on smaller animals (that eat seeds and berries) would fall apart, colorful flowering plants would disappear, and ecosystems would be in critical danger of collapse.

Update on the many threats to bees

There was a time when flowering meadows and other bee-friendly habitats carpeted huge swaths of land. These days, bees must travel much further distances for food, often subsisting on just a few types of flowers, rather than the many types they often need in order to live healthy lives. But there's far more to this story than simply a loss of habitat, and the threats bees face vary depending on the type of bee. Learn more about pesticides, commercial pollination, genetic diversity, and other factors affecting bee health. Read more

The origins of bees

Honey bees and bumble bees have both been around for about 30 million years, and it is likely that their bee ancestors first appeared around 130 million years ago, when flowering plants became highly diversified (the first flowering plant fossils so far found are 135 million years old).

The earliest bees were most likely solitary species, and this is still true of the majority of bee species today. The earliest known social bee lived about 80 million years ago (our oldest bee specimen preserved in amber). This Kinkora specimen (Cretotrigona prisca) is a type of stingless honey bee. There are around 550 species of stingless bees today worldwide (close relatives of honey bees).

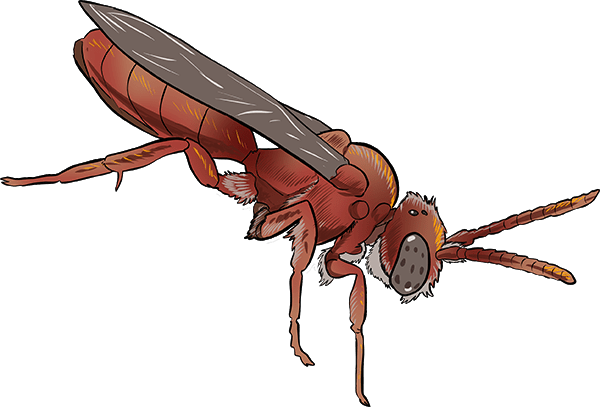

All bees are originally descended from wasps; at some point, some wasps discovered that pollen would make a nice protein-rich substitute for meat, and started feeding their young an exclusively vegetarian diet. It is possible that the early Cretaceous proto bees fed on tiny flower-loving insects known as thrips, whose bodies were coated in protein-rich pollen. This is thought to be how bees made their transition to a diet of pollen and nectar.

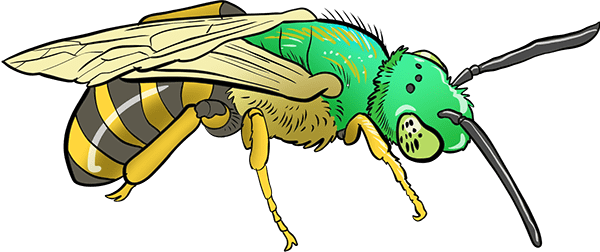

Many ways to collect pollen

Bees have adapted a number of ways in which to transport pollen to their nests (adult bees feed pollen to their young, whilst themselves drinking nectar for energy… honey is simply evaporated nectar, with bits of pollen tossed in for good measure).

Bees have adapted a number of ways in which to transport pollen to their nests (adult bees feed pollen to their young, whilst themselves drinking nectar for energy… honey is simply evaporated nectar, with bits of pollen tossed in for good measure).

Honey bees and bumble bees pack their pollen neatly on their hind legs (moistening the pollen grains with a bit of nectar to stick them together).

Leaf-cutter bees do not have pollen baskets on their hind legs, instead carrying pollen in specially developed hairs on the undersides of their abdomens.

Some native bees have specially developed hairs all over their hind legs, and look as though they have wooly leg warmers (these bees often make particularly good pollinators, because the pollen falls off their hairs more easily).

Social & anti-social bees

Social & anti-social bees

Honey bees and bumble bees are social and live together, but most bees are solitary.

Honey bee hives are tens of thousands strong (as many as 60,000 to 80,000 bees in one hive). There's one queen bee, a small percentage of male drones, and a majority of female worker bees. The bees in these hives survive winter together by forming a living ’ball’ of bees to keep warm (bees on the outer edge of the ’ball’ continually work their way inwards, while on the outer edge, bees sip honey from their honeycomb, with the queen be safely in the middle, kept warm and fed by her many workers).

Bumble bee colonies also have a queen and workers, but with many fewer bees (in the dozens to hundreds depending on the species). Each fall, bumble bee colonies disperse, with the current season's queen typically dying (along with her workers), and a number of newly hatched young queens mating before each finding her own spot to hibernate underground. The following spring, those young queen bees awaken and found their own colonies with worker bees, up until the following fall when new queens and males are produced.

Solitary bee nests are often found near one another, but each nest is managed by a single female, who lays all the eggs, providing for offspring she will never see (she will die before winter, and her young will emerge the following spring or summer). Sometimes solitary bees choose to become semi-social bees. For instance, carpenter bees sometimes find it advantageous to cooperate (when nesting habitats are hard to come by). In these cases, closely-related bees live together, with a primary queen doing all the foraging as well as the egg-laying, while other subordinate queens protect and guard the nest. Carpenter bees typically live for one year, but when they nest collaboratively like this, the lifespans of the subordinate females can be as long as three years.

Caring bee mothers

There are so many different ways for bees to live. Take tiny Ceratina (bees you’ll find almost anywhere). These little bees nest inside dead stems such as blackberry canes. The mother bee hollows out a long tunnel in the center, forming “rooms”. In each room, she lays one egg and adds food (nectar-moistened pollen). She creates “walls” from the pithy material to separate the rooms (other bees do this too; mason bees with mud and leafcutter bees with leaves).

But Ceratina bee moms go so much further than other “solitary” bees (who leave their offspring unattended in their cells to hatch out alone the following year). Each mother bee chews through all the dividing walls she built each night, checking all her offspring are alright. She then parks herself, stinger outward, blocking the nest entrance.

And she goes further still. She cares for her offspring into adulthood, doing the foraging and providing a home. These younger bees will overwinter together with their mother, before going off on their own the following spring.

Interesting news & articles

Bumble bees are able to acquire new skills and pass them on to future generations! Watch this amazing little video showing them pulling string for a reward. Bumble bees can also learn to play ball!

Bumble bees are able to acquire new skills and pass them on to future generations! Watch this amazing little video showing them pulling string for a reward. Bumble bees can also learn to play ball!

Bees learn while they sleep, and that means they might dream Studies indicate honey bees experience a deep sleep state that helps them retain memories and learn new things. Honey bees sleep between 6-8 hours each night, and even hold each other’s legs as they snooze.

The old man and the bee Explore the mountains of southern Oregon with Robbin Thorp, professor emeritus, on his quest for Franklin’s bumble bee. It has not been seen since 2006, and the commercial bumble bee industry (which transports non-native bumble bees and their diseases internationally) is likely to blame.

How to really save the bees A charming article that delves into the fascinating world of our native bees, exploring their nesting habits and lifecycles, and the simple steps one can take to invite more bees into one’s garden, and support their vital ecosystem contributions.

How the bees you know are killing the bees you don’t An interesting discussion of the impacts of commercially-managed bumble bees and honey bees on the diversity and health of our many, often unnoticed and under-appreciated, native bees (around 4,000 species of which live in the U.S. alone).

Bee Art

Bee stickers, greeting cards and more on my Etsy shop.

All the Buzz!

An occasional email newsletter with seasonal bee gardening advice, curious bee facts, current bee research, and other bee-related goodness.

I only use your email address to send you occasional bee-related emails (opt-out anytime). Read my full privacy policy.

Are bees in danger of extinction?

Are bees in danger of extinction?

Bees have adapted a number of ways in which to transport pollen to their nests (adult bees feed pollen to their young, whilst themselves drinking nectar for energy… honey is simply evaporated nectar, with bits of pollen tossed in for good measure).

Bees have adapted a number of ways in which to transport pollen to their nests (adult bees feed pollen to their young, whilst themselves drinking nectar for energy… honey is simply evaporated nectar, with bits of pollen tossed in for good measure). Social & anti-social bees

Social & anti-social bees Bumble bees are able to acquire new skills and pass them on to future generations!

Bumble bees are able to acquire new skills and pass them on to future generations!